Church of the Immaculate Conception, Longarone

Giovanni Michelucci- Typologies Religious / Memorial Place of worship

- Material Concrete Stone

- Date 1966 - 1978

- City Longarone

- Country Italy

- Photographer Fundazione Michelucci

After neorealism, the return to simplicity and organic architecture, the sixties, the decade of prosperity, brought an unusual formal freedom. Still in need of constructive legitimacy yet eager for aestheticism, the most assertive architects dared at that moment to create sculptural forms which – as in the Baroque period – displayed geometry and construction by means of a deliberate complexity. This gave way to a modern mannerism, one for which form is an expression of the Gestalt rather than the Cartesian discourse; and in which construction is able to find legitimacy in itself, and not merely through economy. Intelligence can afford to explore and disappear into the feeling and lure of technique, into a social postmodernity which precedes what will shortly after be denominated postmodernism in architecture.

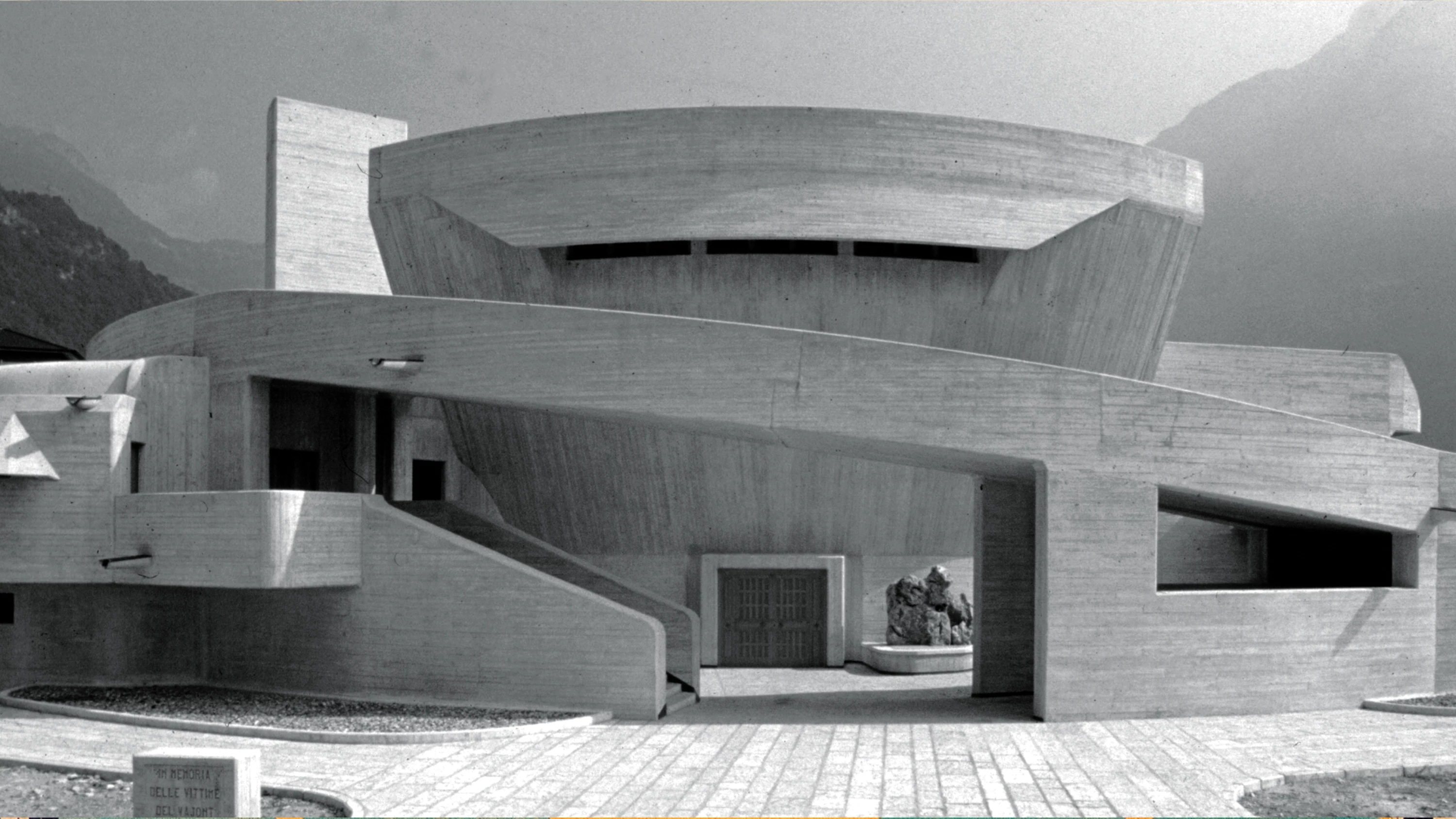

So now the religious building, which had maintained as postwar attitude a voluntary renunciation of the modern architectural glory and Franciscan austerity, claims freedom of gesture. The argument of the work, the drama of eternity – that with the rationalists had been cut down to the essential – takes on again the grandiloquence of the Catholic theater. Modern expressionism and rhetoric to persuade about the importance of contents instead of dialectics to justify them. A church at the foot of the mountains that wishes to be an amphitheater. Double amphitheater, one on top of the other, something that had never been seen before. The church rises as a small concrete stadium on the valley, and the roof above it forms an open-air circus. All this serves to justify the brutalist – in terms of the moment – and loquacious (for their high pitch) treatment of the ramps and catwalks that lead to the stands and roof. Among them, the traditional elements such as the door, the bell or the crucifix arise as superfluous fragments of decoration, and somewhat out of place.

The liturgy here appears to be an excuse to raise a monument to architecture, full of constructive hints and a few Finnish or Hindu references. The circus-temple of Longarone bears witness to the aesthetic vocation of a narcissistic and prosperous society. Something that the Sciascia of the Todo modo alluded to when he caustically wrote on architecture and sociology, the two great impostures of our times. The nobility of cathedrals should make man shudder for fear of the Almighty who reveals himself in them, and for the joy of sharing so much light and majesty for free. But the concrete and stone of Longarone, at the foot of the mountains, are more likely to share a feeling of loneliness...[+]