Photography is both document and fiction, faithful register of reality and deliberate narration of a story. The same can be said about the photography of architecture: from silver salts to digital bytes, its means and tools have allowed us to portray buildings and cities with the objectivity that its technical nature guarantees, and at the same time with the subjectivity implicit in the eye that frames, separating from the magma of the world whatever deserves being represented. There are many ways of seeing, and those of us belonging to the generation that shaped its critical gaze with John Berger and Susan Sontag know that there are no innocent images, just as there are no photographs of buildings or landscapes without both the luminous traces of objects and the blurred trail of intentions. A picture is a story, and what appears in the frame is just as meaningful as what is left outside.

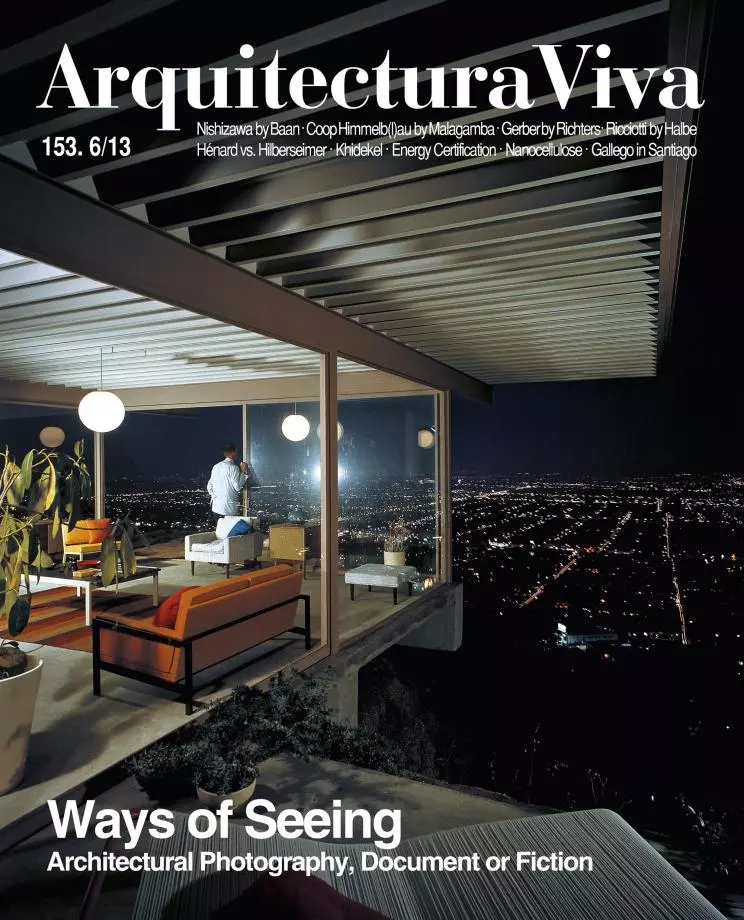

If architects have turned into photographers to capture their own work and that of others – using the camera to replace or complete their traditional sketchbooks –, photographers have become true architects while interpreting with their own eyes the ideas underlying built forms, turning the lens into another tool of this old trade. In the same way, architectural publications have used photographic images – as in the past treatises used engravings – to give muscle and countenance to the bare skeleton of texts, giving visual persuasion to the silent music of words, and in the process being inevitably sequestered by the seduction of sight. From the small Minox 35GT with which this editor took the cover photograph of the first issue of Arquitectura Viva, twenty-five years ago, to the vast technical means of professionals today there is an abyss that draws us insensitively towards spectacle.

After all, photographers today are the most influential architecture critics, both for the works they choose to document and for the way in which they depict them, so it is their agenda and their gaze that establish the guidelines of the global architectural conversation. Transforming critical discourse today probably demands approaching images in a different way, resisting the paramount dominance of the eye and redirecting visual thinking, which, besides being a useful instrument to understand the world, is almost inseparable from the training and instinct of architects, and perhaps also their best and most unique skill. In the end, it is difficult to resist the luring labyrinths of vision, so we shall keep on walking in the company of photographers, and continue yielding to the fascination of images. Paraphrasing Baudelaire, “hypocrite photographer, my likeness, my brother!”