The Optimism of the Will

The popular revolt against the behavior of the elites and the global transparency created by Big Data are features of a year we try to register without resentment.

This Yearbook first appeared in 1993 in the form of a book. From 1994 on, it has come as a double issue of AV magazine. My articles were also printed, simultaneously, in the Yearbook of the newspaper El País (until its publication ceased last year), and the titles, in sequence, suffice to give an abbreviated account of those two decades. The end of the 20th century was presented with a bittersweet taste, reflecting the economic and emotional fluctuations – annus mirabilis, annus horribilis – of the emblematic year 1992: titles like ‘Philippine Farewells,’ ‘Three Feasts and a Funeral,’ ‘Seasons of Transit,’ ‘European Eves,’ ‘Memories and Mutations,’ and ‘Globalization and its Discontents’ led to ‘Welcome to the Latest Spectacle’ of the year 2000. But from then on the tone was uniformly somber, and after the inevitable ‘Towers of Doom’ of 2001, ‘The Black Planet,’ ‘Signs of Strength,’ ‘Fracture Lines,’ ‘Troubled Times,’ and ‘Globe without Governance’ chronicled the military and ecological crises of the early years of the 21st century in a spirit of despair. On the eve of the Beijing Olympics, ‘Asia’s Dawn’ of 2007 brought some brightness, but the crisis sparked by the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers was bound to darken the following years: ‘A Shock in the System,’ ‘Here Comes the Cold,’ ‘Days of Penitence,’ ‘Precipice and Protest,’ and ‘Sinking Nations’ document five years of unyielding bleakness. After that litany of texts tinged by the Gramscian ‘pessimism of the intellect,’ maybe the time has come to weave the story with some threads of the ‘optimism of the will.’

The year 2013 has been replete with conflicts as atrocious as the civil war in Syria and catastrophes as tragic as Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, but it also lends itself to a chronicle with a note of hope. The growing energy autonomy that fracking gives the United States has weakened its ties with Saudi Arabia, facilitating agreement on Iran’s nuclear program and creating better perspectives in the wasps’ nest of the Middle East, origin and cause of the advance of an Islamic fundamentalism that France curbed in the Magreb with its decisive military intervention in Mali. The popular revolts in Istanbul, São Paulo, Cairo, or Kiev made social or political demands heard by elites incapable of distributing the fruits of emerging prosperity more fairly, and caught up in espionage intrigues that – in the wake of Wikileaks – Edward Snowden’s revelations helped to map, revealing the importance of the huge masses of information that digital companies handle: Big Data is here to stay. As regards personalities, the unprecedented abdication of a Pope gave the tiara to a Latin American Jesuit committed to social causes, and Pope Francis’s coming into the picture is as welcome as the Berlusconi’s ousting, which coincided with the reelection of the almighty Merkel. And in Spain, scandals that have eroded the prestige of institutions, increasingly aggressive secessionist tensions, and events like the tragic collision of the iconic AVE bullet train or the failure of Madrid’s bid to host the Olympics coincide with the first signs of economic recovery and a vigorous clamor for political regeneration, demanded by many movements and organizations.

The information flows and data traffic controlled by technological companies cover many contemporary needs, but are a menace to privacy, as the massive revelations of WikiLeaks or of former CIA analyst Snowden have shown.

For architecture, always attentive to the buzz of the real estate market, the Spanish year was marked by the restructuring of property debts in the balances of lending institutions through a ‘bad bank,’ the return of international investment to take advantage of lower prices – the American firm Hyatt bought the Agbar Tower in Barcelona to turn it into a hotel, and the sovereign fund of Abu Dhabi purchased the Foster Tower to house the offices of the petroleum company Cepsa –, and the melting away of the expectations created by the Olympic bid and the prospects of a huge recreational complex, Eurovegas; all this in the context of a still depressed building sector and a heap of negative hype for the profession, which made Santiago Calatrava the scapegoat of the crazy bubble years. But the crisis has also had the effect of stimulating the internationalization of big and small firms, encouraging a qualified emigration of professionals and professors, and instilling in the young generations a spirit of austerity and solidarity sure to be the foundation of the recovery to come. Rejection of the waste associated with iconic architecture is de rigueur today in Spain and the rest of the West, however much icons still thrive in the Gulf, the ex-Soviet republics, and China, or even in a Tokyo that has chosen a sculptural stadium by Zaha Hadid as emblem of its 2020 Olympic Games.

European architects completed major works outside the continent, such as Renzo Piano in Fort Worth or Zaha Hadid in Baku, but also in their own countries, including BIG in Copenhagen or OMA in Rotterdam.

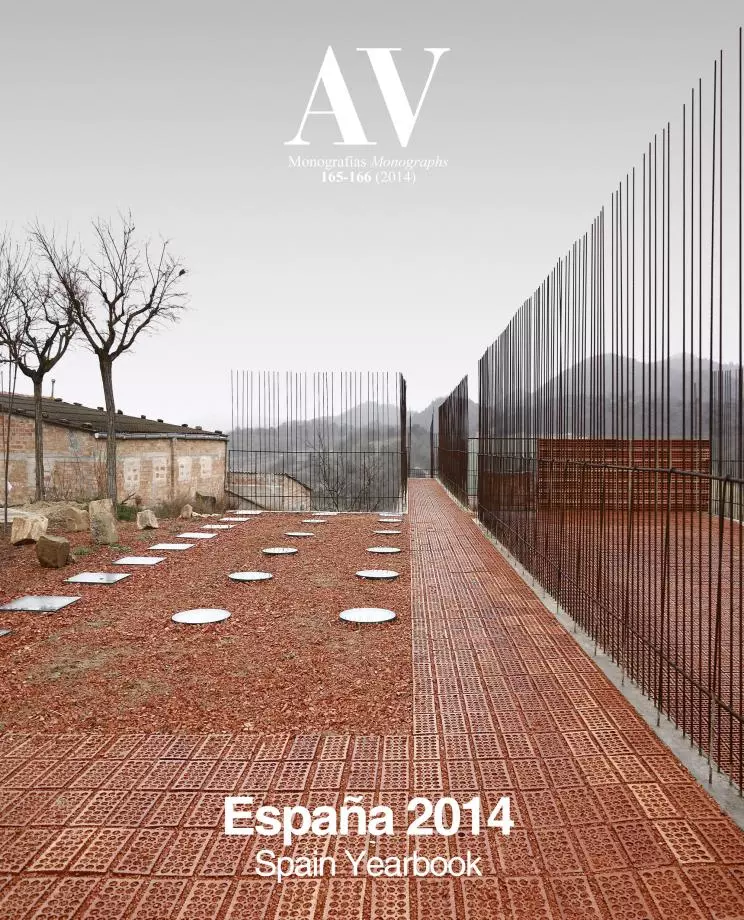

Great cultural works like that by Hadid herself in Baku or by Coop Himmelb(l)au in Dalian are inevitably part of the chronicle of the year, as is Steven Holl’s residential development in Chengdu or the colossal De Rotterdam complex by OMA, which simultaneously finished the Shenzhen Stock Exchange. But this narrative must also include superbly technological airports like Fuksas’s in the same Shenzhen or Foster’s in Amman; as well as museums, elegantly sophisticated like Herzog & de Meuron’s PAMM in Miami or Ricciotti’s MuCEM in Marseilles; cleverly blending into existing contexts, such as BIG’s at the docks of Copenhagen or Lacaton & Vassal’s Palais de Tokyo in Paris; or rich in laconic references to 20th century architecture, like the JUMEX in Mexico, by Chipperfield, or the enlargement of the Menil in Fort Worth, executed by Renzo Piano with admirable deference to the splendid original by Louis Kahn. Here in Spain, outstanding works were completed by the veterans Manuel Gallego in Santiago de Compostela and Gerardo Ayala in Madrid, besides Rafael de La-Hoz also in the capital, Paredes & Pedrosa in Ceuta, or RCR in Olot; but no list can omit certain projects abroad, and here we should at least mention those by Antón García-Abril in Mexico City and Eduardo Arroyo in Vienna, two unique works by architects with experimental attitudes.

In the chapter on distinctions, exhibitions, and events, Spain celebrated the coinciding centenaries of Alejandro de la Sota, Miguel Fisac, José Antonio Coderch, Antonio Bonet, and the still living Rafael Aburto; the world those of George Candilis, Constantinos Doxiadis, Amancio Williams, Mario Roberto Álvarez, and Kenzo Tange; and the fiftieth year of the Berlin Philharmonic coincided with the fortieth of the Sydney Opera House and the twentieth of the Carré d’Art in Nîmes, which Foster marked by curating a major art exhibition occupying the entire building. Renzo Piano was named Life Senator in Italy and other architects received the profession’s most coveted awards: Toyo Ito the Pritzker, David Chipperfield the Praemium Imperiale, Peter Zumthor the RIBA Gold Medal, and Thom Mayne the AIA’s; while the Wolf went to Souto de Moura, the Tessenow to Campo Baeza, and the conservative Driehaus to Thomas Beeby. Specific works were distinguished too: Larsen & Eliasson’s Harpa in Reykjavik with the Mies, Witherford Watson Mann’s Astley Castle with the Stirling, Toni Gironès’s Megalithic Center with the FAD, and Cruz & Ortiz’s Rijksmuseum with the International Spanish Architecture Award, given at the Senate Palace by Prince Felipe, who expressed his support of a profession in trouble. Finally, a year that bade farewell to Hugo Chávez, Margaret Thatcher, and Nelson Mandela also lamented the passing of the architects Paolo Soleri, Clorindo Testa, Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, Javier Carvajal, Henning Larsen, Fray Coello de Portugal, and Christian de Groote, the critics Ada Louise Huxtable, Roberto Segre, or Ulrich Conrads, and the photographers Baltazhar Korab and Yukio Futagawa, and it would not be rhetorical to close by saying that all will live on in their works, writings, and images.

The year that celebrated the centenaries of Miguel Fisac or Alejandro de la Sota also saw the completion of works by RCR in Olot, NO.MAD (Arroyo) in Vienna, and Ensamble Studio (García-Abril) in Mexico City.