Next Stop Teruel

Teruel exists, but only at times. It existed with Mudejar splendor in the 13th century, a briefand shining medieval moment that began with a town chapter in 1176 and culminated with the magnificent towers, of the first quarter of the 14th century, which UNESCO has included in its heritage of humanity list. It existed tragically in the terrible winter of 1937-1938 as the scene of one of the Spanish Civil War’s most devastating battles, suffering an assault that reduced a good part of the old city to rubble. And it aspires to exist, in this uncertain transition from 20th to 21st century, manifesting itself in demands for infrastructure, developing a theme park to expose its paleontological wealth, and summoning leading architects to defend the historic city from the automobile and prepare it for the arrival of the high-speed train.

In the project to remodel the monumental front of the city, Chipperfield’s team keeps its austere traces, introducing a core of elevators in the retaining wall and extending a stone carpet down to the train station.

The Mudejar moment was extraordinarily materialized in the towers, a series of slender brick prisms profusely adorned with geometric filigree and glazed ceramic, whose delicate profiles form part of the old quarter’s magical silhouette. Built by Muslim masons under Christian dominion, and therefore miscegenations from the start, it would be na‹ve to consider them the product of a harmonious coexistence of cultures in a medieval Spain where conflicting religions simply tolerated one another at times when lack of settlers with which to repopulate territories rendered ethnic cleansing unfeasible. Attached to churches and spanning the streets and gates of the city, the towers follow the model of the Almohad minaret and rise as warnings and emblems of religious and civil power in a borderland town. The then called “peaceful Moors” (the word ‘Mudejar’does not appear in records dating before the late 15th century) lived in quarters dedicated to subordinate tasks, and would in time give rise to the Morisco problem. The Moorish inclinations of some renaissance aristocracies, of a good part of the romantic bourgeoisie, and of almost the entire body of contemporary intellectuality cannot hide the fury of the peninsula’s medieval confrontation, that to this day arouses the elegiac rancor of Osama bin Laden’s lieutenants, and is expressed by the violent elegance of Teruel’s towers (the minaret slenderness of which, incidentally, is achieved through the same structural scheme of NewYork’s Twin Towers: two concentric square tubes).

Lucky survivors of the brutal battle of Teruel, which made the city a coveted symbolic objective for both sides, the Mudejar towers were in the post-war period inserted in an urban landscape efficiently and intelligently reconstructed by the architects of the Devastated Regions program, who invoked the imperial and Herrera-style triumphalism of granite and capitals for the great seminary, but for the rest of the buildings chose the traditionalist regionalism of stone, brick, galleries and eaves that characterizes the civil renaissance architecture of the Ebro Valley. So long in frontier land between Christians and Muslims, Teruel then had the misfortune of occupying a strategic position – a wedge that threatened to separate Catalonia from Valencia – in the battle line of the Spanish Civil War, and its devastating capture by the republican army in January 1938 was celebrated there by Prieto, Negrín and La Pasionaria as a victory of far-reaching material and psychological importance. Just six weeks later, the city’s falling back into the hands of the troops of Franco would give it a symmetrically symbolic charge, a “martyr” like Oviedo or Toledo – Ceuta’s Muslim community would that same year ask the three cities for ashlars to be laid as the first stones of its great mosque – and “adopted” by the Caudillo, like Belchite or Brunete, for reconstruction at the termination of the conflict.

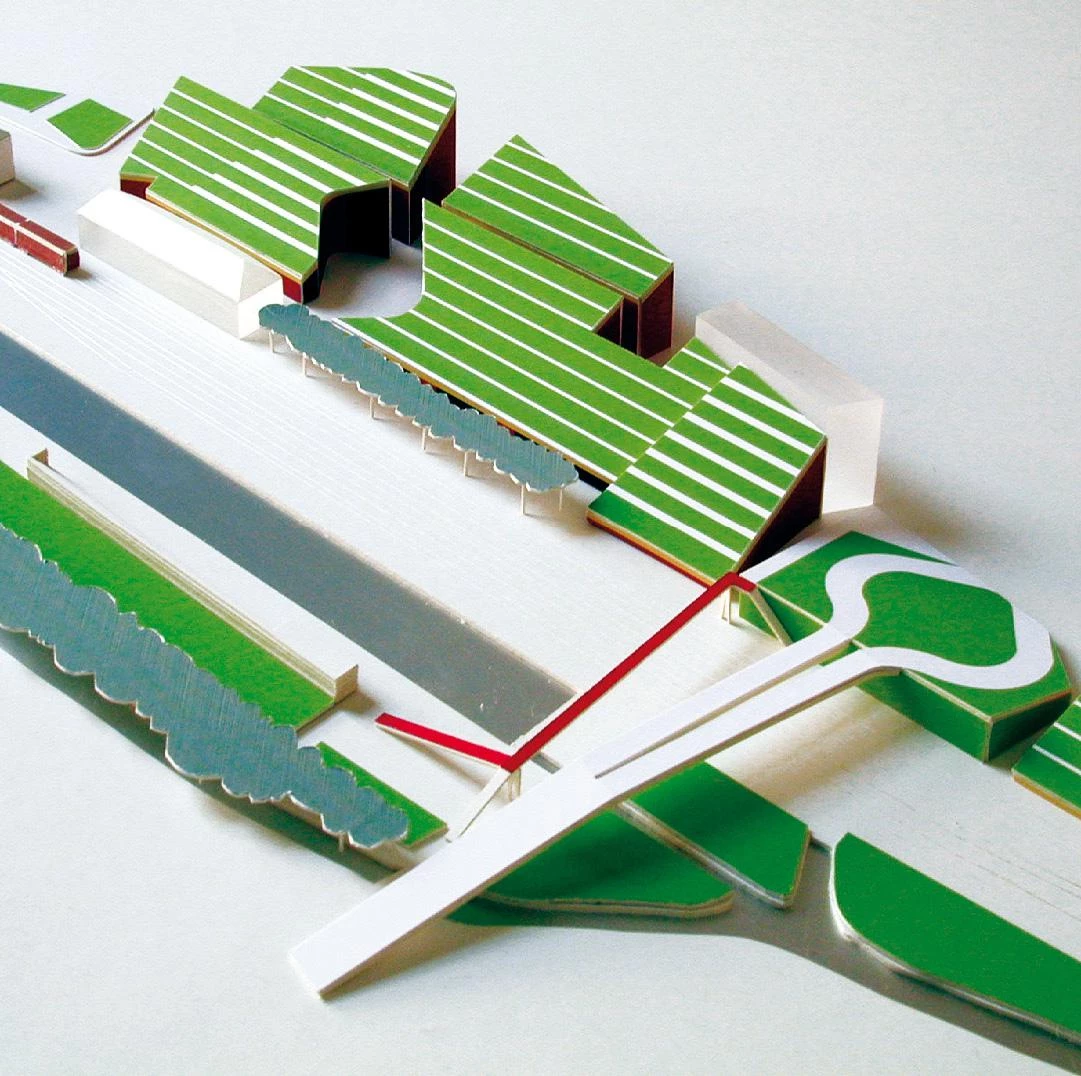

Moreno Mansilla & Tuñón proposed a large cruciform building covered with photosensitive sunflowers over the river and railway tracks, with a tramway to bring passengers from the train station to the historic center up in the hill.

In their new interpretation of a Teruel that in the first third of the century had been modernist in its private constructions and regionalist in its public buildings – but where the finest works, in the tradition of the Pierres Vedel who erected the Los Arcos aqueduct in the 16th century, had been left by engineers like Carlos Castel and José Torán, creators of the neo-Mudejar staircase that in 1920 connected the urban core to the station; like Fernando Hué, designer of the viaduct that linked the medieval quarter to the new extension of the city, whose 79 meters in 1931 marked the record for spans in continuous vaults; or like Juan José Gómez-Cordobés, author of an ignored masterpiece of rationalism, the Casa del Barco of 1934, an experimental concrete construction whose nautical profile rises over a spectacular barbican that is also the best lookout over the city – the architects of the reconstruction inclined towards the indigeneous models that then constituted the less aggressive kind of historicism. The city owes them their sober, respectful schemes which, in light of subsequent mistakes, including the chaotic enlargements of recent democracy, must be judged with more respect than irony. Those architects proceeded in the manner of surgical repair, and an obligation to measure up with them has necessarily befallen the teams convoked to refurbish Teruel’s west facade: a beautiful cornice over the meadow of the Turia River, crowned by the Mudejar towers, that stretches from the seminary to the viaduct, some of whose elements constituted part of the reconstruction of the forties and fifties.

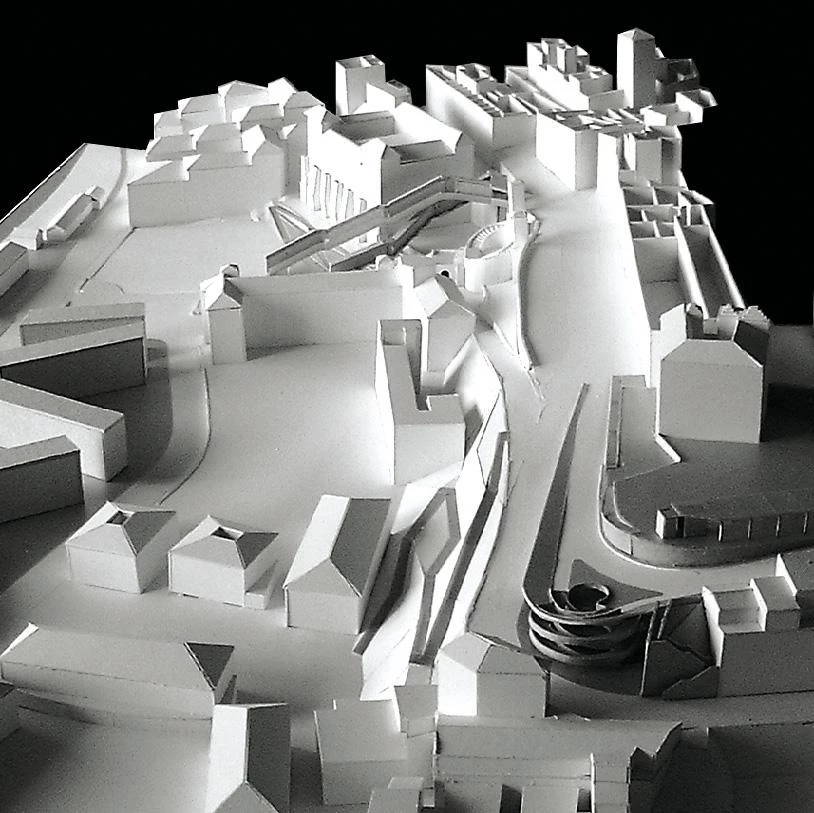

The winner of the recent competition is the most austere entry, a project of the British David Chipperfield, in conjunction with the Spanish firm b720. With mannerist sensibility and the skill of an acupuncturist, it perforates the huge retaining wall beside the old Carmelite convent, now the seat of the Aragonese government, to accommodate an elevator core whose monumental and luminous gate is accessed from the train station by way of a carpet of stone. It highlights the grand neo-Mudejar staircase as if it were a formidable sculpture, pedestrianizes the urban balcony of the Óvalo without obstructing the passage of vehicles, and accommodates under a new roundabout a very efficient parking lot that facilitates access by deterring internal traffic: a painstaking exercise in historic surgery that is quite familiar to an architect who is simultaneously building on Berlin’s museum island and Venice’s San Michele island. The second prize went to the imaginative project of the Madrid team of Tuñón, Moreno Mansilla and Prior, which includes a cruciform building covered with photovoltaic sunflowers over the railway tracks and the river, with a streetcar to span the level difference between the station and the old quarter. Finally, the third prize was awarded to the Zaragoza architects Pemán and Franco, who submitted a complex proposal that involves burying traffic underground and a linear parking system beneath the Óvalo. Unfortunately there was no acknowledgment for the lyrical project of Juan Navarro Baldeweg, who, surely disoriented by the guidelines, put more emphasis on the future development of the area beside the station than to any immediate intervention in the cornice. Neither was credit given to two Catalan proposals: the exhibitionist, sculptural escalators by Martínez Lapeña and Torres, and a disconcerting collage of fragments and ruins by Batlle and Roig.

The remaining projects ranged from the collage of fragments to urban sculpture: Batlle & Roig (left), Pemán & Franco, Navarro Baldeweg, and M. Lapeña & Torres (right, top to bottom).

The mythical scene of the Mudejar coexistence of Christians and Muslims also staged the dramatic story of the Amantes, driven by adversity and destiny to die of love. The emblematic toponym of the civil conflict’s storm of hate was also the venue of a formidable postwar reconstruction process that made it an example of urban renaissance. But the contemporary symbol of marginalization and abandonment only endeavors to tie up seamlessly with that network of flows and places that we call Spain. Teruel has lived its drama of love and its tragedy of hate. It must now simply play a demanding role in the amiable comedy of a conventional country.