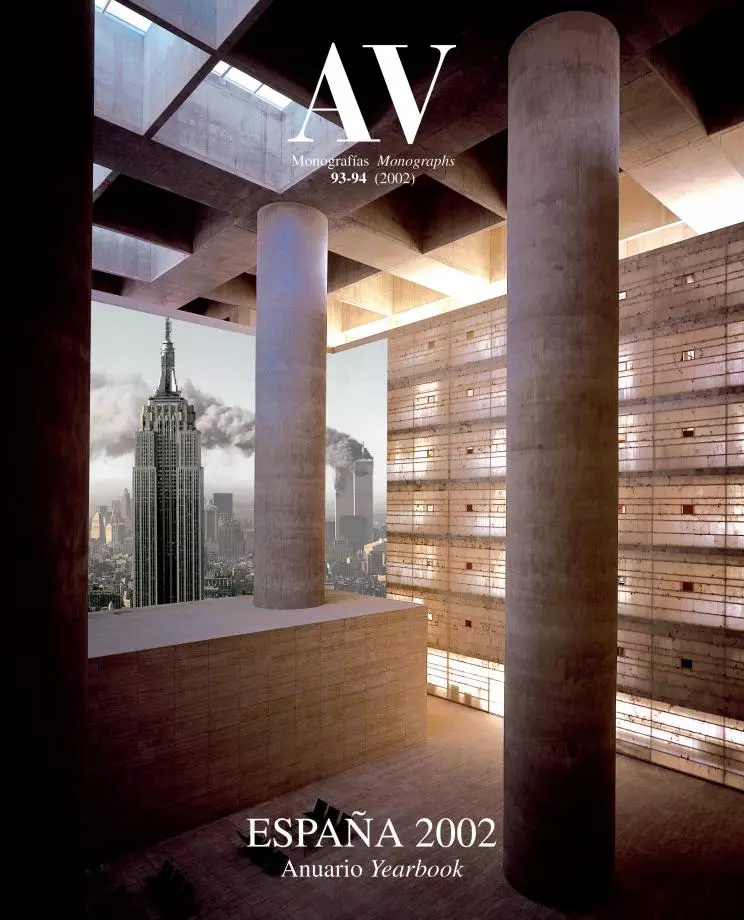

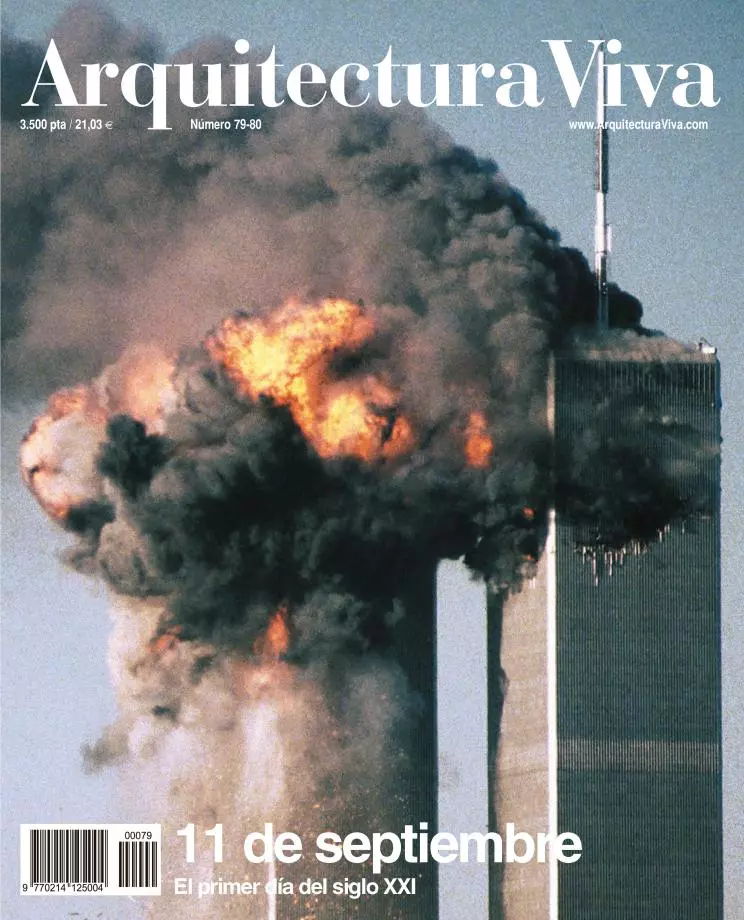

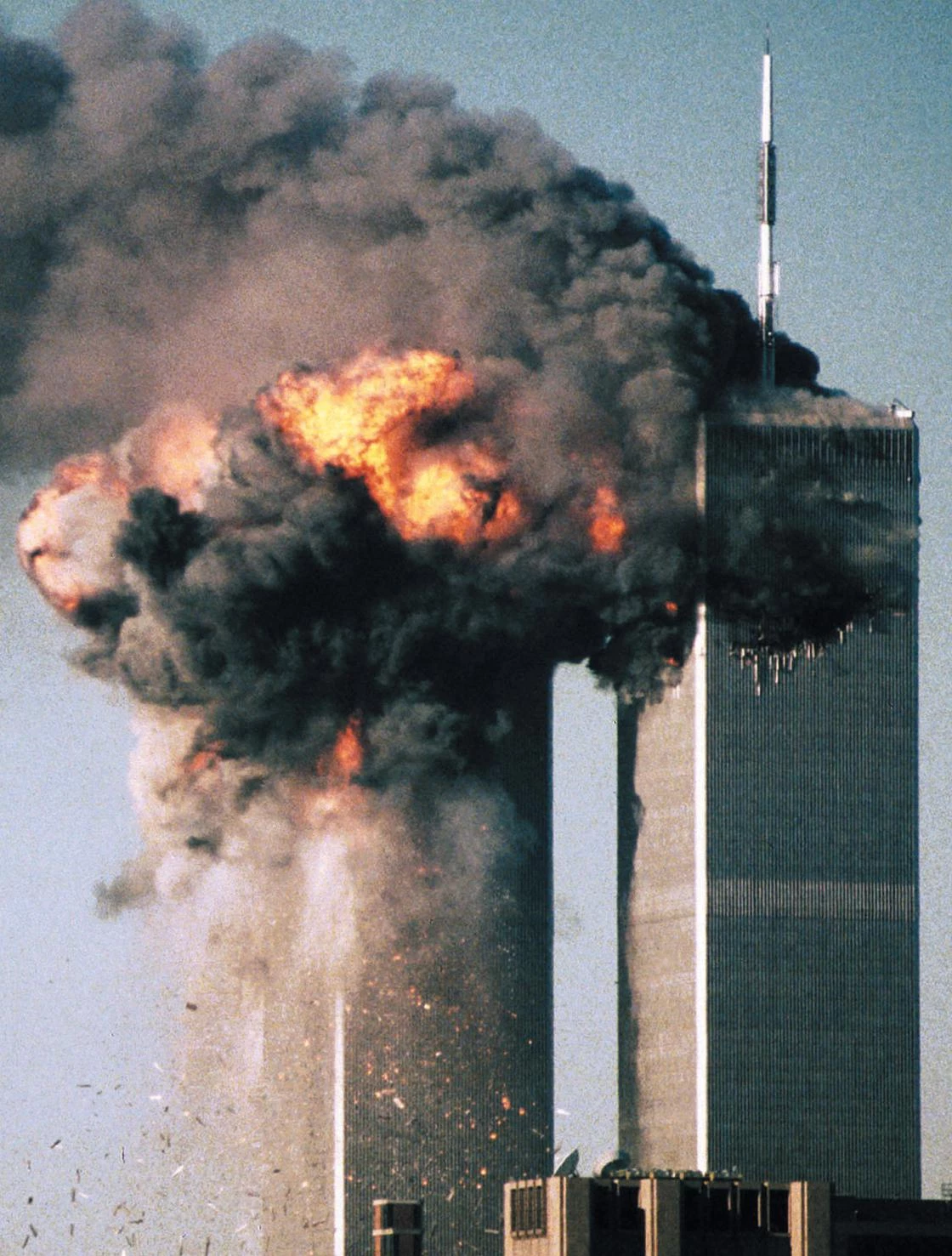

With the rubble still fresh, Manhattan’s future is being debated. Should the World Trade Center be rebuilt? Real estate pragmatism demands the replacement of the office space that was extirpated from the economic heart of the planet. Assertive patriotism clamors for an imperious emblem that would express its tenacious resistance to the challenge of terror. And elegiac desolation wants a commemorative monument to honor those killed and crystallize the memory of the tragedy. New twin towers could be all three things: offices, symbol, and memorial. But a mimetic reconstruction of the WTC would veil the three purposes with the dark opacity of blindness, arrogance, and nostalgia.

Though the one million square meters of office space lost after the terrorist attack must be recovered, both the New York real estate market and the economic situation advise to do so in a gradual manner.

Blindness because, while true that the million square meters of vanished office space must be rebuilt, there is nothing to indicate that this should be done immediately, nor in the same way as before. Companies will undoubtedly weigh up the prestige of occupying an icon against the risk of being in a target, and everything indicates that the process of urban cauterization may be gradual. Manhattan still has 8 million square meters of office space, and New York as a whole as many as 26 million, many of which have been emptied thanks to the dot.com crisis. This, combined with the deceleration of the economy, had already made rental prices drop as much as 30%: both the dimension of the real estate market and the economic cycle offer to cushion the brutal impact of 11 September. Although some of the affected firms have moved to nearby New Jersey and Connecticut towns, whether for good or provisionally, the complete resumption of stock exchange activity just six days after the attacks proves the regenerative capacity of the social and technological fabric of this muscular metropolis. One has to be blind to judge the Twin Towers as indispensable either to the financial survival of Wall Street or to the economic leadership of Manhattan.

The Manhattan skyline cannot be reconstructed exactly as it was: designed in 1964, the Twin Towers emerged from a radically different technical context, from the structure and services to security.

Arrogance too because, if few question the material, political, and emotional need to rebuild the city as a sure sign of the democratic will not to be defeated by cruelty and panic, even fewer could propose the erection of a facsimile of the Twin Towers without the gesture being interpreted as a stubborn adherence to an inured and luminous past, frozen in a photograph. But neither can we pretend nothing has happened by reconstructing Manhattan’s silhouette, nor does it seem to make sense to build again skyscrapers designed back in 1964, in a radically different technological context – from the structures and services to the communication systems and security. The World Trade Center towers rose 110 floors, but today it is hard to justify a skyscraper of more than 80 storeys on grounds which are not purely symbolical, and the fact is that buildings comparable to them in height have not gone up in the United States in over two decades. Though widely unappreciated by architects, who dismissed them as simplistic in their minimalism and as trivially decorative in their neo-Gothic friezes, the colossal scale and metaphysical elementality of the two prisms made the towers an icon of NewYork City, and this emblematic popularity is also invoked when their possible restoration is compared to that of so many European monuments and historic places devastated by military conflicts or natural catastrophes. But the Twin Towers are neither Warsaw nor Lisbon’s Chiado. Here collective memory is attached to an eminently technological and economic artefact, and anachronical mimesis can only be understood as the product of a combination of defiant arrogance and infantile obstinacy.

Finally, nostalgia because while the hurtful maximalist call to abstain from building on a site indelibly marked by tragedy is only conceivable in a context of economic decadence and urban decline, the demand to reconstruct the towers mimetically, in tribute to values shared by the victims, reeks of the schmaltzy, cloying perfume of a rhetorical and naive staging of the triumph of life over death. In the final analysis, the best commemoration of death is that which does not interfere with the free course of life: that which allows remembrance and mourning without imprisoning survivors in the glass cage of frozen time. In Oklahoma, where in 1995 another fanatical and criminal delirium blew up a federal building and killed and hurt a large number of people, and after a long public debate that served as collective lesson and therapy, the citizens decided on an altogether new building, one with no relation whatsoever to its predecessor and no commemorative purpose, while a memorial of the tragedy rose in the vicinity. For NewYork City, in a similar manner, such meditated option seems more appropriate than a simplistic, nostalgic, autistic, poor imitation of a past that on a Tuesday of a September vanished before the astonished eyes of the world.

The city’s public figures have energetically clamored for an immediate reconstruction of the damaged area, but few have followed the path opened by ex-Mayor Ed Koch when, just hours after the attack, he proposed a literal recreation of the World Trade Center – “We’ve got the plans.” Most favor a new project accompanied by a memorial (like Philippe de Montebello, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who has suggested that the jagged remains of the tower facades be left as they are). Incumbent mayor Rudolph Giuliani himself soon qualified his vigorous initial calls for reconstruction, explaining that he had really been referring to a regeneration of the devastated zone, and among New York architects, only Disney factotum and Yale dean Robert Stern – who compares the categorical prisms of the Twin Towers to the pyramids of Egypt and the sculptures of Donald Judd – has declared himself in favor of their reconstruction. In a survey conducted by The NewYork Times, the majority of his colleagues proposed the building of something different, albeit no less daring or visible. Among them are Bernard Tschumi, who looking to the future instead of the past contemplates something “bigger and better”; Terence Riley, who recalling the formidable reconstruction of Chicago after the fire of 1871 speaks of another skyscraper, “bigger and more innovative”; and Richard Meier, who in defense of a magnificent New York demands a complex of buildings that would be “a city symbol as powerful as the World Trade Center towers were.”

Compared with the 110 floors of Yamasaki’s skyscrapers, it seems difficult today to justify a building of more than 80; for over two decades towers of such height have not been raised in the United States.

Perhaps the most revealing opinions are those of three architects of successive generations, as they perfectly express the attitudes mentioned at the start: the real estate pragmatism of the nonagenarian Philip Johnson, partisan of “building at least the same volume of office space destroyed”; the assertive patriotism of veteran Peter Eisenman, defender of “reaching the height of the old towers, without letting this attack on western culture and values make us step back”; and the elegiac desolation of the young partners Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, who moved by the destruction of the city’s skyline are opposed to its regeneration, since “the void is powerful –it would be a tragedy to eliminate elimination.” In any case, both the braking of the economy and the atmosphere of brewing war suggest that it will take some time for a decision to be made. The new constructions may be financed by insurance companies, but neither the WTC’s public proprietor, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, nor the private les-see of the complex, the developer Larry Silverstein, will have the last word in a project that so profoundly affects the collective pride of an injured nation.

Honoring the memory of the victims should be made compatible with the regeneration of the devastated area, but the opinions about the future of Ground Zero are not unanimous, as is reflected by the views of New York architects of three different generations: pragmatic that of the elderly Philip Johnson, patriotic that of the veteran Peter Eisenman and elegiac that of the younger Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio.

Whatever the decision, the catastrophe of the Twin Towers does not herald the extinction of the skyscraper, in the same way that it is far from becoming an epitaph for commercial aviation. If traveling by plane will be more difficult and uncomfortable in the future, so will living or working in a skyscraper; if airline companies are already finding themselves caught in an ever more complex technical and political landscape, so will builders of highrises now have to confront a hyper-regulated world, with less symbolic lure for potential occupants, and this will have the effect of delaying, requiring revision of, or altogether cancelling numerous projects. Still, we will neither stop flying nor stop building skyscrapers. Chemical terrorism in the tunnels of Tokyo’s subway did not make cities close down underground transport, threats of bacteriological terrorism on drinking water have not interrupted our urban supply networks, and the impact of the Boeing 767 planes on the World Trade Center will destroy neither air transport nor the vertical city. Land travel and the horizontal city will be more popular, but nothing will replace the haughty Tower of Babel aspiration in collective imagination.

Many remember that the same King Kong who carried Fay Wray to the top of the Empire State Building in 1933 brought Jessica Lange to the summit of the Twin Towers in the 1976 remake. What new landmark will the great gorilla climb in the next version? The architect Cesar Pelli, who in the eighties built the World Financial Center’s cluster of towers flanking the giants, writes to me about the loss of human lives: “The towers I designed have suffered much damage. But when the pain is so huge, the damage on buildings, though mine, is secondary. I designed them in such a way that they would be a visual support for the Twin Towers. Now they are on their own and seem larger. I hope two new great towers go up on the same spot. That would be the best symbol of the reconstructive power of a democracy.” Right now the dice are rolling and the swords are up, while we hold our breath to hear the rumor of war winds. We will not know Manhattan’s tomorrow until the tears have cooled the rubble.