Open Eyed Justice

The new judicial buildings completed in France and the United States resort to signature architectures that do not conceal the current crisis of justice.

Justice is no longer blindfolded. Both France and the United States are erecting effusively visual constructions to patch up a cracked system, and Spain – attentive at once to the judiciary experiments of its northern neighbor and to the litigation spectacles of the USA – is laying out whole cities of justice to remedy, through buildings, the evils of a defective structure. But more architecture does not mean more justice. The signature works that are cropping up do not reflect the abstract neutrality of blindly dealt justice, nor do the new bureaucratic citadels seem to endow the law with the unbiased centrality it ought to have in the civic scene. After the superstar judges and mediatized lawsuits, we have star architects and media buildings – when what the blindfolded eyes of justice clamor for are sober, anonymous constructions that express the sedate dignity of a law that is the same for all. And in response to the contemporary degradation of a judicial administration overwhelmed by a multiplication of causes, we get a labyrinthian proliferation of specialized precincts – when what social cohesion requires is an incorporation of justice into the firm and flexible fabric of the existing city.

In France, the new generation of law courts has not prevented the revolt of judges, a thousand of whom gathered in March in front of the Hôtel Matignon to demand the reorganization of the judicial system, gravely damaged by an accumulation of ordinary proceedings and by the difficulty of pursuing major economic and political offenses. Initiated in 1992, the program for the modernization of the judicial system has yielded, among other things, the courthouses of Richard Rogers in Bordeaux, Jourda & Perraudin at Melun-Sénart, Christian de Portzamparc in Grasse, Yves Lion & Alan Levitt in Lyon, Architecture Studio in Caen, Claude Vasconi in Grenoble, and Jean Nouvel in Nantes. But such enormous investment and effort, and such pooling of architectural talent, have hardly improved the image of justice, perceived by most to be disdainful of the weak and deferential to the powerful: justice biased, not blindfolded, that is dealt out from designer buildings more intelligible as expressions of the formal language of their authors than as interpretations of the empire of the law.

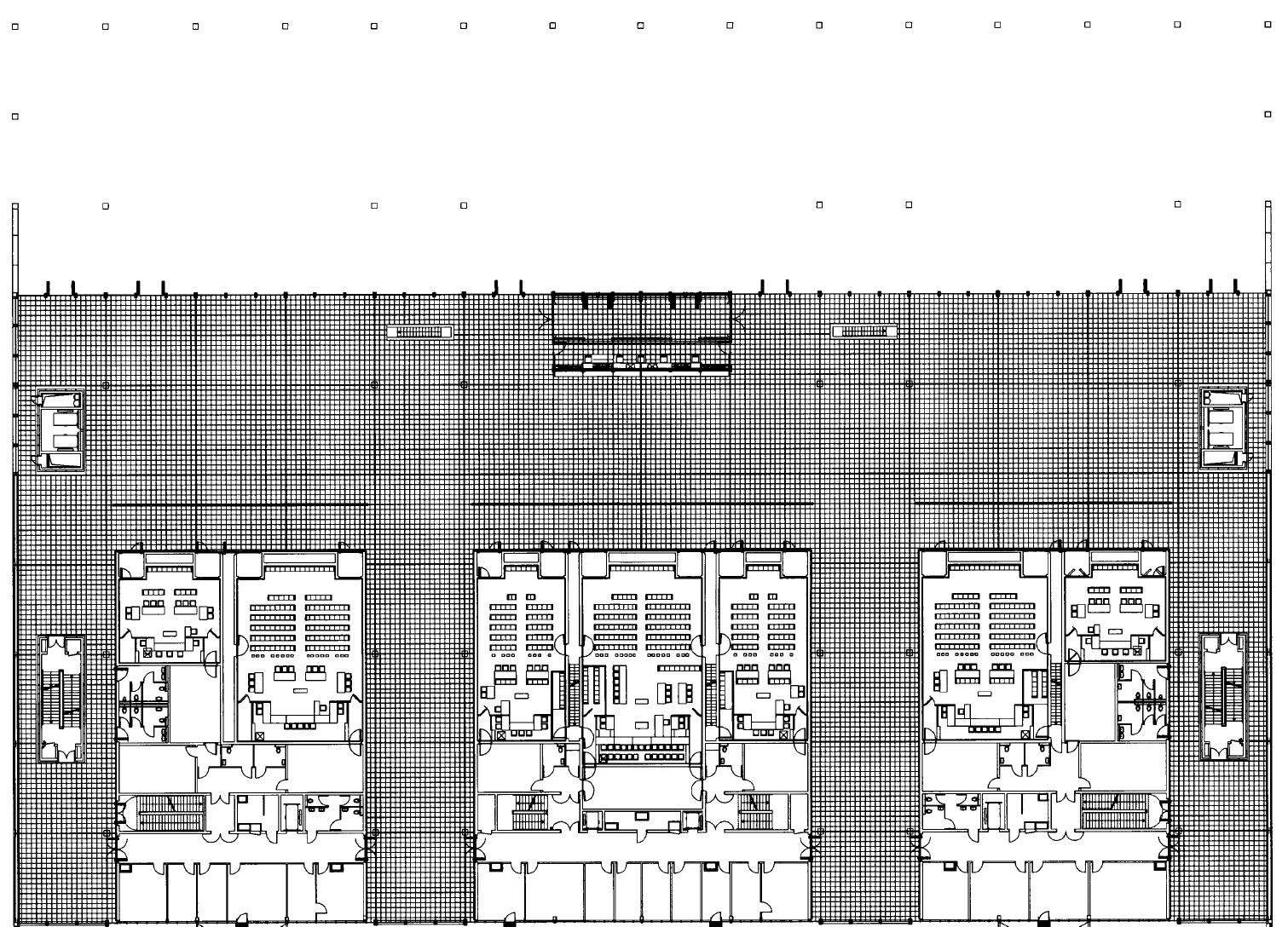

Extreme rigor in the modulation of spaces and homogeneously reflecting surfaces: in the Palace of Justice by Nouvel in Nantes, the judicial process is represented as an implacable machinery.

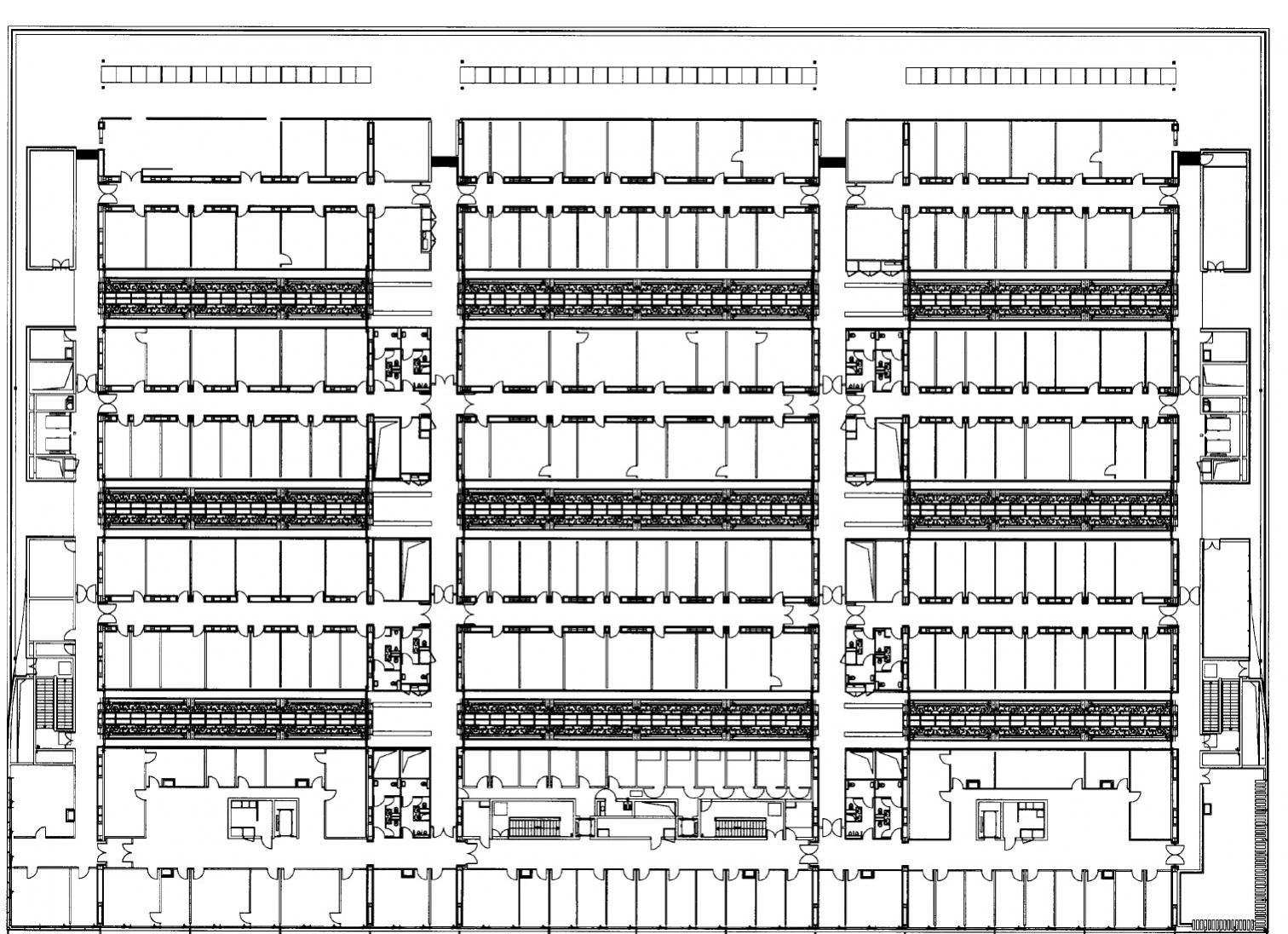

The huge wooden casks containing the court-rooms of Richard Rogers’ Palace of Justice in Bordeaux are, of course, a wink at the region’s wine cellars, but inserting these barrels in an airport-type structure of steel and glass situates the work in the technological and futuristic expressionism of the architect. The metal trees in the main facade of Jourda & Perraudin’s judicial premise in Melun-Sé-nart present a version of the classical portico that is usual in court buildings, but the familiar branched geometry is actually more evocative of the previous projects of the partners.And the monumental ellipse and fragmented volumes of Christian de Portzam-parc’s law courts complex in Grasse may be an attempt to blend it into the discontinuous urban scheme of the city’s periphery, but one inevitably relates such choreographic decomposition to prior works of the architect such as the dance school of Nanterre or the City of Music in Paris.

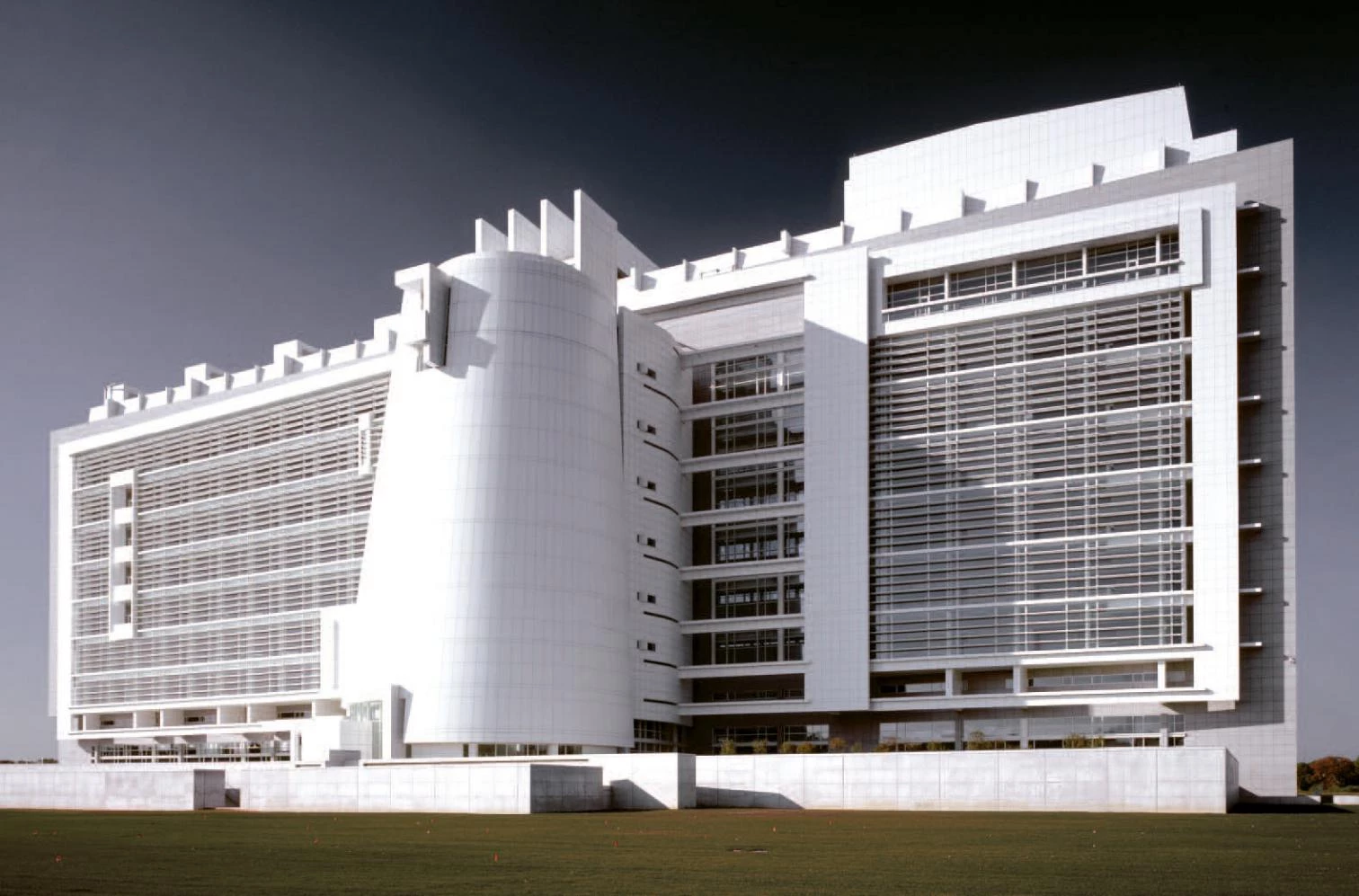

Designed by Richard Meier, the building for the Courthouse of Central Islip, New York, is one of the flagships of a Federal Program for Excellence in Design that the United States started in 1994.

Only Jean Nouvel, in the Palace of Justice of Nantes, transcends his personal language to deliver an ominous, cruel and sublime interpretation of justice, which he incarnates in the obsessive modulation and maniatic perfection of a building constructed of geometry, darkness, and reflections. Shunning the amiable populism that considers the citizen a consumer of justice and customer of judiciary services, Nouvel has raised a colossal portico, at once Greek and Miesian, that takes your breath away, and behind it a large foyer of black polished granite that feigns abysses and a series of rather hermetic courtrooms that make the redwood cladding seem glacial. Abhorred by many of its users, who deplore its threatening look, this is neither a smiling nor a warm work of architecture. But in its frosty fire burns a passion for justice that is closer to the rigor of Saint-Just than it is to the temperance of “Ethica Nicomachea”, and that does not allow itself to be mixed with the more trivial expressions of architectural authorship. Here Nouvel does not give us a characteristic Nouvel, but a reflection on society, equity, and power. And this is what makes him a great architect, even in an excessive and failed project like this one.

Nothing of the kind can be found in the United States, where a federal program of design excellence, launched in 1994, has materialized especially in new court buildings, among these two by Richard Meier, in Central Islip (New York) and Phoenix (Arizona). The fruits of this operation are currently on display in Washington, D.C., in an exhibition whose curator insists on comparing them to the governmental projects of the Roosevelt administration in the thirties and the City Beautiful Movement of the early 20th century. However, the modest results of this commendable effort speak more of the extraordinary limitations of public initiative in the United States, as well as of the poor moment that American architecture is traversing. The two Meier works are tediously predictable – the former reiteratively Corbusian, the latter equipped with the solar protection portico to be expected in desert area. And here, too, authorship prevails over critical reflection, something to regret in a country that settles political disputes in courtrooms and turns trials and executions into spectacles.

From the French effort to modernize the image of Justice have emerged the high-tech canopy of Jourda & Perraudin in Melun-Sénart, the ellipse of Portzamparc in Grasse or the classical portico of Nouvel in Nantes.

Meanwhile, in Spain, a motley program involving cities and palaces of justice has given rise to a large number of competitions. Some of them have already announced winners: Almería (Ayala), Málaga (Frechilla, López Peláez, Herrero & Seguí), Ciudad Real (Vázquez Consuegra) or Valencia (Batuecas). Others will soon: Toledo, Salamanca and Murcia. It is still difficult to discern any pat-terns, but it does look like here, too, judiciary malaise is being fought with architectural medication – a remedy that cures many ailments, but which we should not consider snake oil, no matter how flattering it may be for architects to feel, just for once, more part of the solution than of the problem.