Islands of Islam

The Islamic world wavers between the colossal display of symbolic works and the functional austerity of the projects selected by the Aga Khan Prize.

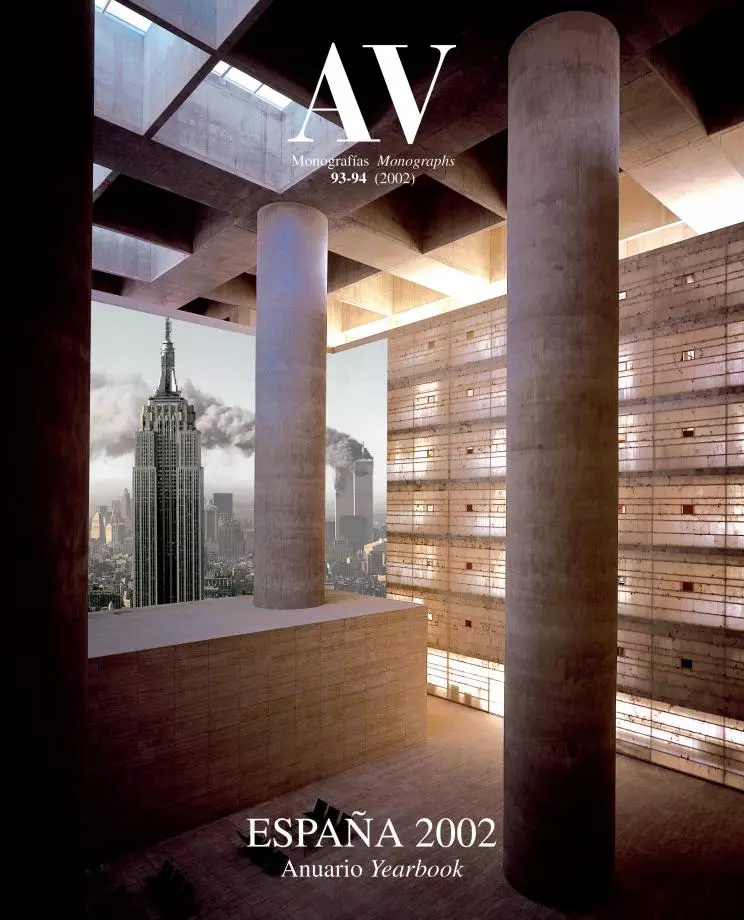

The silamic continent is an archipelago. If architecture is to provide an example, the image reflected in the dark mirror of Muslim construction is a landscape fractured into abnormal splinters, a warm sea of poverty and violence dotted with islands of insulting opulence and waste. Such a cracked panorama is perhaps a consequence of the episodic attention we give to the billions of people who live between the Moroccan Atlantic and the Indonesian Pacific – ever perceived, as they are, in the reflecting pieces of the broken glass of crisis. But it may also come from the despotic inequality of societies that have struggled, in vain, with the 20th century. A year ago in Dubai, the world’s tallest hotel was inaugurated, a tower shaped like a sail rising on a man-made isle in the Persian Gulf, which constituted a new milestone in the carica-turesque ostentation of oil sheikhs; and this month, in the Syrian citadel of Aleppo, the winners of the Aga Kahn Awards were presented, nine exemplary projects which place architecture at the service of life in the cracked universe of Islam that stretches from Guinea to Malaysia. It is difficult to imagine more contrasting manifestations of contemporary Muslim culture, or better examples of the abyss of abandon that yawns amongst the fortified insular redoubts of its economic and political elites.

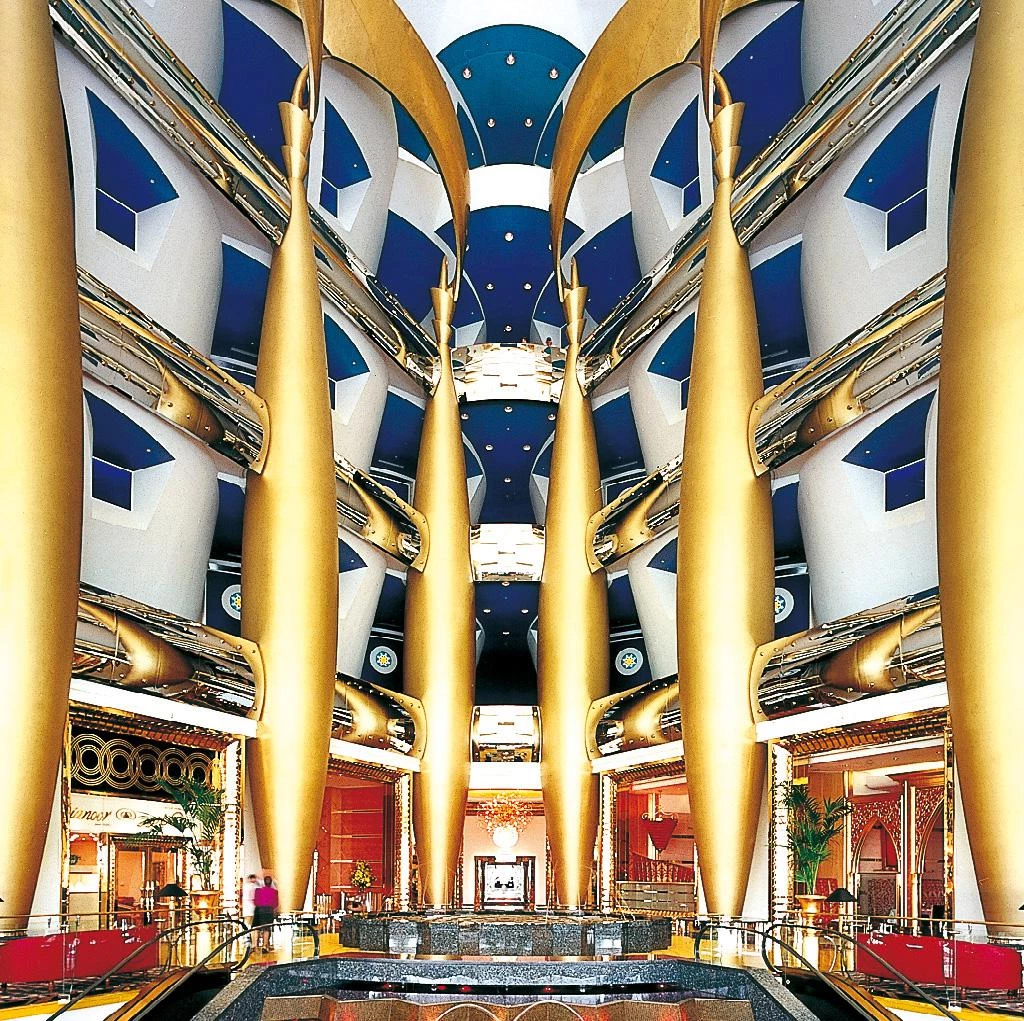

With a height reaching 320 meters, a sailboat profile and interiors wrapped in gold leaf, the Burj al Arab hotel illustrates the shameless ostentation of the architectures promoted by the oil sheikhs.

Promoted by the sheikh Mohamed ben Rashid as a new symbol of Dubai, the Burj al Arab or Tower of the Arabs soars to an altitude of 320 meters, more than any European skyscraper – the continental record is still held by Frankfurt’s Commerzbank, at 259 meters. Built facing a beach, on a man-made island that enhances security and makes it all the more exclusive, the hotel is braced against wind and seismic risks through an extravagant external structure that stresses its sail, cimitar, or half-moon profile, crowning itself with the panoramic fold of the restaurant in the mast and the aerial tray of the heliport over the translucent bellows of the fiberglass facade that illuminates the vertiginous atrium. Here, 2000 square meters of 22-carat gold leaf clad a ridiculously oneiric decor that beats the worst kitsch of Las Vegas, providing access to equally excessive standard duplex units charging over $1000 a night and suites priced nearly $8000. The figurative fantasies of the designers – a team of the British consulting firm of W.S. Atkins headed by architect TomWright, who has since then specialized in theme parks – reaches ludicrous heights in a project whose cost the client prefers to keep a secret. With its nautical skeleton and fountains of a thousand and one nights, the sheikh wanted to erect a tribute to Sinbad the Sailor, the hero of this “coast of pirates,” but with such offensive ostentation and vulgar taste, he has instead come up with the best emblem of the Gulf’s oil-rich and corrupt monarchies.

In its arrogant and trivial aplomb, the Hotel Burj alArab is a caricature of the at once self-withdrawn, hedonistic and spectacular narcissism of our times, and a symptom of the cynicism of theArabian Peninsula’s Wahhabite elites, who finance religious fundamentalism while raising exhibitionist monuments to thematic luxury. In the sixties and seventies, the postcolonial construction of many Muslim nations was expressed through parliaments. In Dacca, the American Louis Kahn built the capitol center of the future Bangladesh as a geometric fortress of concrete surrounded by a pit, with a unique mosque over the entrance that emphasizes the institution’s deference to the Islamic faith. And in Kuwait, the Danish Jørn Utzon carried out a national assembly that successfully expressed the country’s peculiar oligarchical-tribal organization, with its bazaar-evoking floor plan and the roofs like large canvasses of concrete. But in the eighties and nineties, the frustration of social expectations and the failure of laic reformism brought about a rise of radical Islam, with a religious renaissance that sparked a proliferation of mosques, and a brazen capitalism materialized in buildings showing the power of petroleum. The piously titanic mosque of Casablanca, built on King Hassan II’s orders to placate the ever increasing numbers of fundamentalists in Morocco, and the rhetorically colossal Petronas Towers of Kuala Lumpur, conceived by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed as an icon of the economic boom and Islamic traditions of Malaysia, represent two geographic, typological and symbolic extremes of an effervescent and fractured cultural universe.

While the tide of Islamic fundamentalism rises, Egypt has built a secular and pluralistic symbol: designed by the Norwegian team Snøhetta, the Library of Alexandria will be the largest bibliographic center of the Middle East.

Having lived through the socialist and pan-Arabic episode of Nasser, and unrelentingly persecuted radical Islamism after Sadat’s assassination in 1981, Egypt is perhaps the only country in the region that nowadays can dare to put up as secular and pluralist an emblem as the new library of Alexandria, the huge leaning discus designed by the Norwegians of Snøhetta which celebrates the classical past of this Muslim city and is due to open in April 2002. Meanwhile, the triennial Aga Khan Awards provide the best architectural expressions of an Islam that combines social sensibilities and the defense of its roots with the desire for economic modernization. The nine winners of the eighth edition – which will share the $500,000 prize that makes the Aga Khan the best endowed of all architectural distinctions, and which were selected by a jury graced by the artist Mona Hatoum and the architects Ricardo Legorreta, Glenn Murcutt and Raj Rewal – sprinkle the Muslim world’s geography with model projects that should inspire emulation.

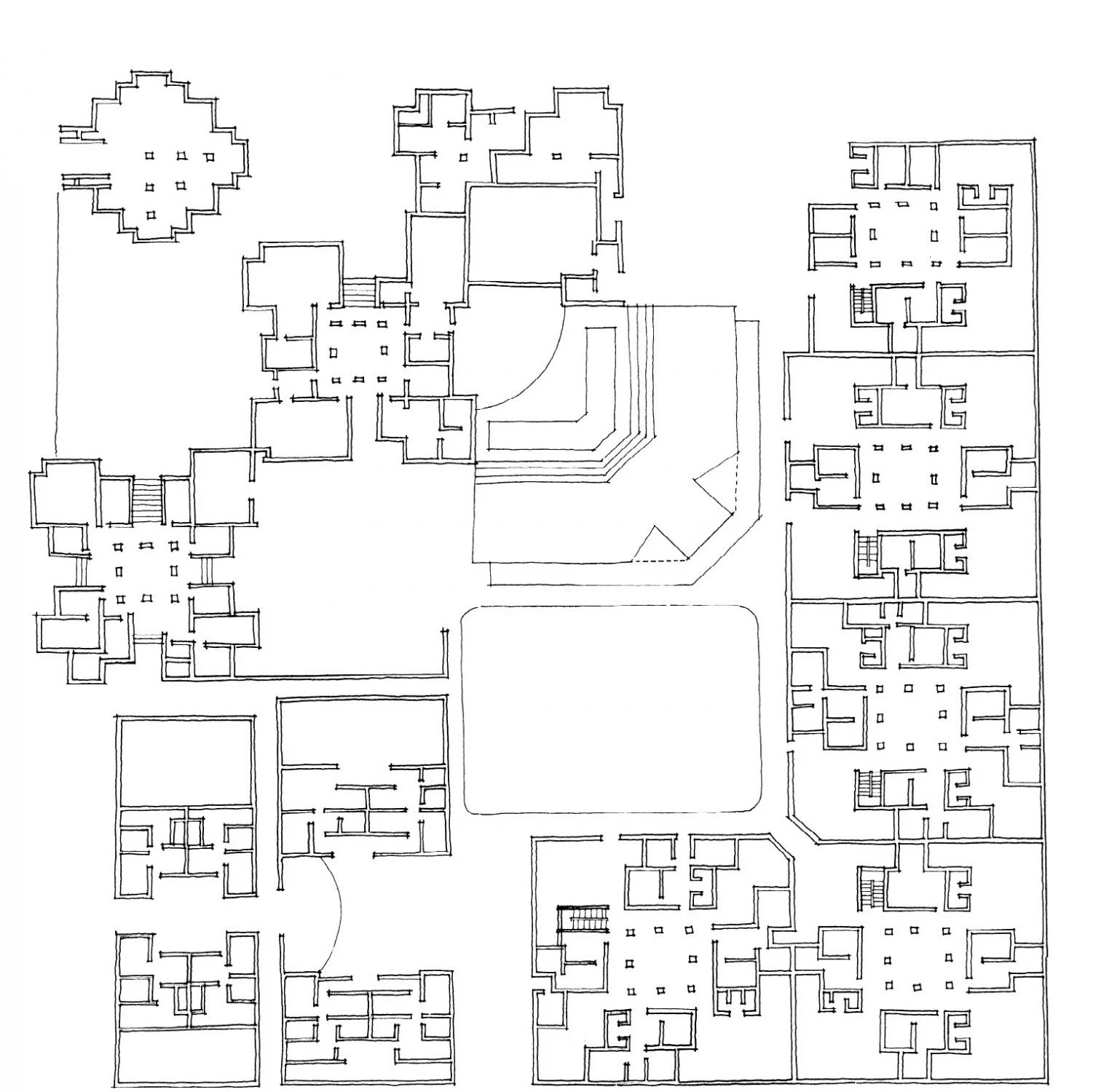

From an agronomy school in Guinea by the Finnish office of Heikkinen & Komonen to a hotel on Malaysia’s rainforest coast by the Australian Kerry Hill, and from a rural planning project in the Moroccan Atlas to a center of appropriate technologies in an Indian valley by “barefoot architects,” several of the works feted are about improving the rural environment, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, through agricultural techniques and nature-friendly tourism. Others, mostly in the Far East, choose to address the endemic problems of cities there through heritage and culture. Hence the program for the restoration of historic buildings in Iranian cities or the new cultural park of Tehran; so too the Nubio Museum in Asuan, a work of the Egyptian Mahmoud El-Hakim, or the university social cen-ter in Antalya, by the Turk Cengiz Bektas

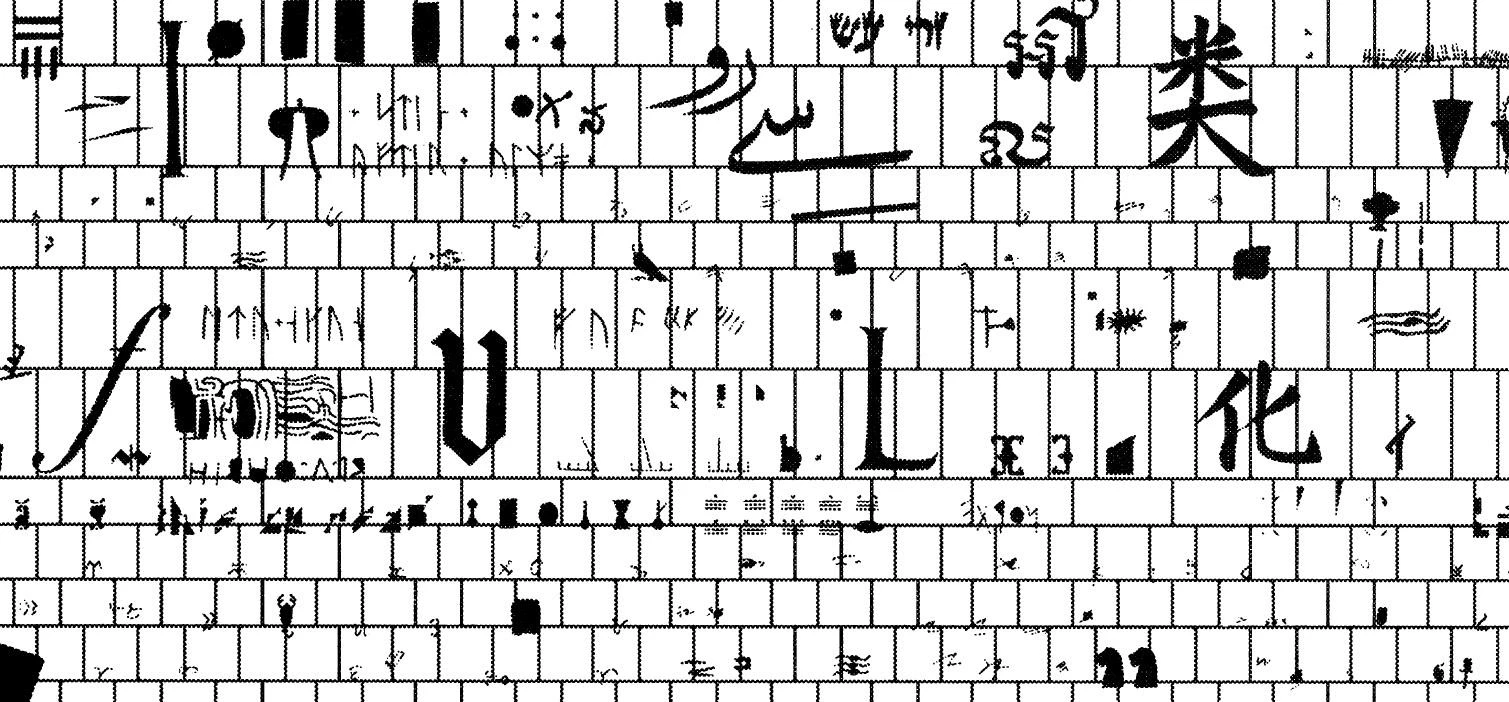

Conceded triennially since 1977, the Aga Khan Awards (below, three of the projects distinguished in the last edition) are the best platform for the diffusion of Islamic architecture with a social and cultural purpose.

Finally, a project situated in the Jordanian city of Aqaba serves as a reminder of the interminable drama of that part of Islam: the orphans’village developed by SOS Children is a small redoubt of houses and gardens whose maze of granite, shades and breezes endeavors to protect the early lives of the innocent victims of a conflict with sure culprits. This luminous isle of refuge from the violence of the world is the reverse of the insular ostentation of the Dubai hotel. The Islamic archipelago is more diverse than we would be made to think by the synchronized tune of AlYazira, a media island which is fabricating a virtual continent in Hertzian space.

Comunidad rural, Tilonia, India Rural community, Tilonia, India

Restauración de edificios históricos, Irán Heritage restoration program, Iran

Aldea de SOS Niños, Aqaba, Jordania SOS Children hamlet, Aqaba, Jordan